Editing is an important part of a photographer’s job; it has the power to completely alter how an image looks when done to the extreme. As such, editing techniques are prone to being overused rather than serving its intended purposes.

In this article, I address questions in relation to the propriety of photo editing, in both digital and analogue spaces, from the perspective of a professional photographer.

I will also share tips and examples on how to edit photos like a pro, including top mistakes to avoid.

If you find this helpful, SUBSCRIBE to my channel via the box on the left to make the most out of my blog! Also, do share it with people who might be interested. Shoot me an email/ DM to share your thoughts too.

Also, Pin this article to your Photography Editing boards in Pinterest if you find it helpful!

Do professional photographers edit photos? Why?

Yes. Professional photographers mostly shoot in Raw, which is a file format NOT intended for final output. Even if an image is flawless, technical adjustments still need to be made, such as lens distortion, vignetting, colour profile and white balance. Besides, professional photographers are often put in difficult shooting conditions which make it unlikely that an image turns out so perfect that it would not benefit from photo editing.

You might want to stop for a minute and think about what it means to be a professional photographer.

What are professionals hired for? The ability to push a button on a camera?

I would say photographers are hired for their ability to execute on a creative vision by producing photographic material, the only restriction being to abide by the industry code of conduct (and the law, of course).

So whatever means, really, whether or not that involves photo editing.

People wonder if pros edit their photos presumably because editing is seen predominantly as a remedy to imperfections in-camera.

This is a rather misleading notion because firstly, as I mentioned above, there are corrections that need to be done regardless of merit, like correcting lens distortions and vignetting.

Secondly, at risk of over-generalising, your photos cannot be really good without post-production.

The biggest reason for shooting Raw rather than Jpeg is that Raw files retain as much detail as possible for manipulation, which means that the file will resemble the scene as-is by large.

But the job of a photographer is to materialise a creative vision, which often deviates from the actual scene. So something must happen to bring the photos closer to what was envisioned.

Not only do I find it strange that there is this stigma against editing, but I do think that photo editing is a respectable art that falls well within the job scope of a photographer.

On many occasions I actually headed to cafes with fellow photographer friends and we edit photos together - we are newspaper photographers, the least ‘creative’ of all photography genres.

In other genres, big name photographers often sit down with an elaborate team of retouchers to work on the editing.

This should sufficiently illustrate how photo editing is an integral part of the craft, and therefore the answer to the question of whether professionals edit their photos is a big fat YES.

In the following sections, I will demonstrate the kind of edits that are very much necessary for each of my images to go through, and also explain the rationales for making them.

How heavily do professional photographers edit photos?

Just enough to bring a creative vision to life. Professional photographers edit photos with a clear understanding of the creative intent at hand, and only make adjustments that are really necessary in achieving the vision. Technical adjustments tend to be standard across the board, like straightening, contrast adjustments, lens corrections, whereas advanced manipulation depends on the brief.

Experienced photographers will unanimously agree that with photo editing, less is more.

If you really know what you are doing, you don’t need much to polish an image, that is if you have a strong image to begin with, which concerns another area of a photographer’s competency.

Also, having gone through countless edits, professional photographers understand that you are actually causing some level of damage to the image via every adjustment you make - every step is a trade-off between the improvement brought about by the editing and the loss in quality.

The more edits you add, the less likely the benefits would justify the damage caused - the law of diminishing returns apply, if you will.

So the overarching principle is that we do the minimum that is required to get the images to where they need to be in accordance with the creative direction from the client.

Photographers shooting different genres would vary a little in terms of how much editing they do, but let’s begin with the basics, which photographers across most genres tend to do.

Technical adjustments that are highly targeted at technical flaws would generally be the starting point.

In this category of edits, you go through stages like setting the lens profile to match your lens, straightening the horizons, correcting the perspective of the image if it was skewed to begin, and select the appropriate colour profile, which happens to be ‘Adobe Standard’ for me.

Cropping also happens if required. Sometimes if unsure about the framing, I tend to shoot wider so that I can decide on the final crop when I could take the time to think through it during editing.

Other times, I find myself shooting under quite a bit of physical restraint and cannot afford the luxury in the heat of the moment to perfect the framing before pressing the shutter.

Brightness adjustments are also most certainly performed by most pro shooters.

Cameras, as much as they are becoming very powerful machines today, cannot see as well as the human eye.

There is a limit to how many shades of brightness the camera can record, otherwise known as the dynamic range.

This has nothing to do with skill - photography is always about compromises. It is a skill of making the best compromises.

There will be situations where the lighting is very high in contrast and the photographer has to prioritise one area of the image at the expense of others, knowing that the balance can be altered in photo editing.

A typical example of this would be to deliberately underexpose the frame by 1 stop in-camera to preserve bright highlights, and raise the shadows in post-production.

In other words, properly exposed images will still benefit from brightness adjustments.

Properly made Raw photos are essentially properly made compromises, which at the end of the day are still compromises.

So editing (itself another act of compromise but that’s another story) is there to counteract some of the compromises made in-camera.

Colour adjustments mostly apply to genres where the creative vision generally requires stronger colour contrast, for instance weddings, landscapes, food, among others.

In these genres, there is a fundamental need to perform colour correction so that the set of images could serve their purposes.

For instance, when shooting people, the skin tones need to look flattering. Making people look good is basically the key here and therefore the skin needs to look natural and healthy.

When shooting food, the agenda behind is usually to portray the food to be as appetising as possible. As a result, photographers tend to accentuate the colours of certain ingredients in the setup to make the food look more vibrant and appealing.

When shooting landscapes, which could come with a much wider set of intentions behind but most of the time it is to depict the beauty of a place. So photographers tend to boost the saturation of the vegetation and enhance the warmth of any golden-hour type of light.

Photo manipulation mostly applies to genres that are traditionally allowed to be more detached from reality, such as fashion, beauty, fine art photography, among others.

Photo manipulation involves adding or removing things in the raw file, altering their shapes or completely changing their colour, and such types of edits will have to be performed in advanced imaging softwares like Photoshop.

A typical usage of this is to remove blemishes and scars on people’s skin, or smoothen out wrinkles to make the subject’s skin look tender.

Another common application of this is to make the bodies of subjects look thinner and better toned.

It can also be adopted by photographers to remove distractions in the background that do not add to the narrative of the photo.

Even in genres where such extensive editing is general practice, professional photographers will still tell you to keep your edits minimal - the skin doesn’t need to look too smooth, the arms don’t need to look too slim, and the streets don’t need to look too empty.

What program should I use to edit my photos?

Most photographers typically use the Adobe or the Capture One system. These two are deemed to be well-developed ecosystems that are capable of taking on the rigour of a typical professional photographer’s workload. Apart from photo editing capabilities, intuitive cataloguing and smooth photo-proofing are features that set these two apart from the rest of the market.

If you are serious about pursuing photography as a life-long hobby or a career, the single most important thing in considering investing in a photo editing software is whether it is also a great photo manager.

It could be quite costly and logistically difficult to have to switch systems later on down the road so think ahead instead of just looking at the subscription fees.

Your workflow becomes the most efficient when the actual editing and output is integrated into your entire photo process.

Photo organising capabilities

That is, you should be able to set up a workflow within your software of choice that enables you to switch between projects without having to open another window.

So in practical terms, you should be able to view, edit, move, delete, name, rate, tag, export photos within the same browser, without having to exit the current job just to enter another one.

Changes made should also be synced automatically within its infrastructure.

For this reason, I personally have stuck with the Adobe system for years. I view and cull my photos via Adobe Bridge, edit them by opening the Adobe Camera Raw application, and save the photos onto my external hard drives via placing instructions within Camera Raw.

Where necessary, I open Adobe Photoshop directly from Adobe Bridge.

I can basically access all my photos and do anything in relation to photos in lieu of the finder window, such as creating new folders, renaming folders, moving files and others.

Adobe Lightroom operates in a similar fashion, except that it bundles all your photos into a library. There is this extra step to import photos into the Library before it becomes part of the system, which I find unnecessary.

You can think of Adobe Lightroom as the ultimate all-in-one, whereas Adobe Bridge allows for more flexibility in that your stuff could be on various discs.

Check out the bundles Adobe provides for general photography usage via this link.

It will bring you to the page that outlines the softwares, aka Lightroom and Photoshop. Bridge is a free application that will be available if you have any Adobe subscription.

Photo-proofing capabilities

Another consideration, perhaps more pertinent to people intending to start a career doing photography, is the capacity to export photo galleries and share photo samples from within the software.

The tricky bit in sharing photos lies in the fact that it is not feasible to upload the Raw files directly because of their sheer size.

But often, clients would want to have a say in the final selects and some photographers believe that their participation in the selection process enhances customer experience.

Either way, the ability to export a jpeg version of the Raw files is a very technical hurdle you will have to pass if you want to serve clients.

So the software of your choice should be able to support some form of uploading, perhaps to Google Drives, to Dropbox or anywhere else without you exporting the Raw images as jpegs first, and then uploading to the platform on which you then open access to your clients.

Doing it manually means you will end up with a bunch of useless Jpegs of the Raw images sitting on your computer, and spending double as much time exporting and uploading.

As far as I am concerned, both Adobe and CaptureOne has built-in systems that support this feature well.

How can I edit my photos like a professional?

Understand the industry standards and regularly cross-check your own work with those of the professional photographers in your field. Avoid mistakes that lead to amateurish-looking photos, such as adding too much clarity, too much contrast, over-dramatic colours and hues, and creative effects.

Professional photographers typically have their unique ways of doing things that they have developed over the years of practice.

While this is not something you can come up with overnight, there are a few things that if avoided, would save you from years of trials.

Basically, just avoid these mistakes and you are half way there.

Too much clarity

To be honest, speaking of digital cameras today, there is seldom a reason why you would need to add clarity where an image is in focus.

You can see adding clarity as an artistic touch but under 99% of the circumstances, it is seldom going to do much for your photos, if not destroy them.

Here is an image where the clarity was overboard, from my earlier archives. I am going to roast my own photos only because roasting others without their consent is, well, verbal assault.

The surefire sign that you have overdone the clarity is the appearance of haloing near edges. Look carefully at this example above - at the outline of the Blue Mosque and the trees, there appears to be a thin white layer separating them from the sky.

That’s known as the halo effect, where the object appears stands out too much from the background due to an artificial light banding around it.

This is the direct result of adding clarity. To add clarity is basically to add edge contrast. The software would identify edges in the image and boost the contrast of the pixels on the two sides of the edge.

As a result, where overdone, the lighter side of the edge ends up being too light, forming a noticeable layer outside the object, which you obviously do not want in your pictures.

The best way around this is to leave the clarity slider alone.

Too much contrast

Contrast is another slider that professional photographers tend to stay away from.

It is not because contrast is not important; imho, contrast control is a very determining aspect of a photographer’s editing style.

But my issue with the contrast slider is that it changes contrast globally, and somewhat arbitrarily.

If you look at what is happening to the histogram when you increase the contrast slider, the values on the histogram migrate towards both ends of the spectrum: shadows towards blacks, and highlights towards whites. The mid-tones thin out.

This is seldom what a photo needs; usually, only a certain segment of the image needs to be altered. For instance, you may want to darken the blacks without affecting the highlights, vice versa.

If the values naturally congregate in the middle, it means that the scene is a flat scene to begin with, in which case you would want to be especially cautious in adding contrast because it wasn’t there in the first place.

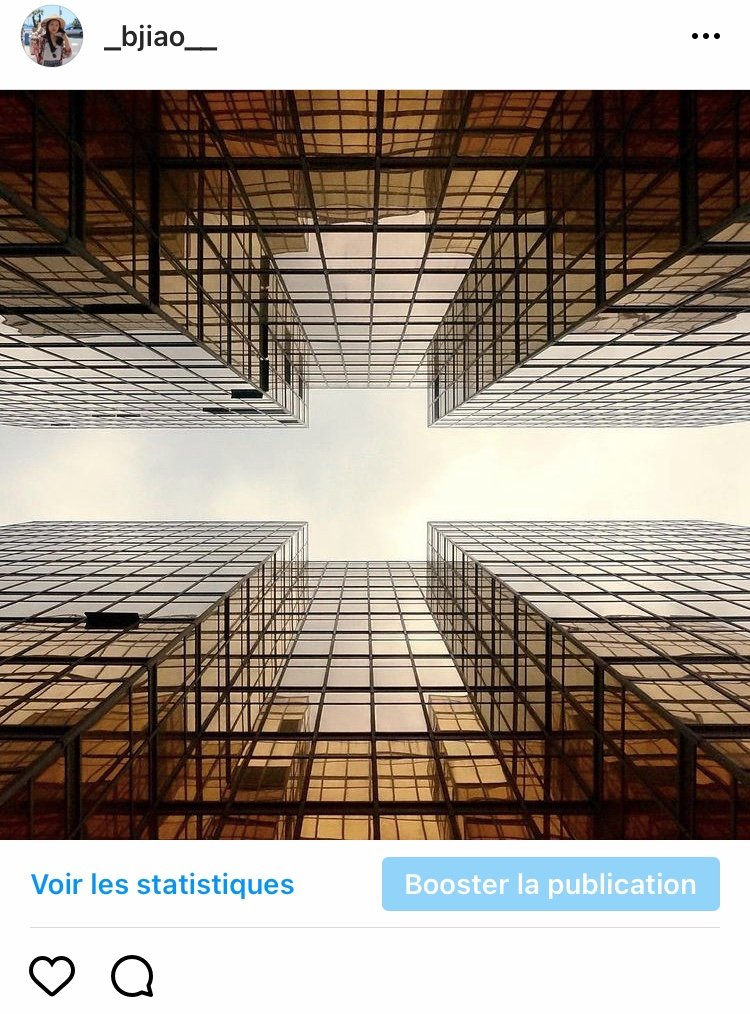

Here is an example of what I mean by adding too much contrast to a photo.

Look at the supposedly brighter buildings to the right. They were under the sun and therefore relatively brighter but there is no reason why there should be no detail in them.

The black bits on the other hand, were exceedingly dark. The shadows under the shields on the wall of the buildings were darkened by too much.

What I should have done, rather than pulling up the overall contrast with just one slider, is to make more targeted adjustments to the corresponding brightness levels of whites, highlights, midtones, shadows and blacks.

Use these sliders rather than the overall slider; beginners typically do not realise this but the overall contrast slider tends to overdramatise images.

Bizarre colours and hues

Call me a purist but I think before we talk about creative expression, what is white should at least reflect as (close to) white in final images.

When colour is being applied in a blanket manner rather than selectively, things start going wrong.

Here is an example of when colour is overused.

I am not sure what exactly happened as this photo was taken when I was about two years into photography.

But I am guessing that I was probably going filter by filter, stopped at one that I think looked alright, basically jumped off the app and made this post.

The filter gave the photo a yellowish, cyanish hue, which in itself is not a problem; the real problem is that even the sky and the clouds looked yellowish; they obviously should not have.

The difficult thing about editing colours is that you get so absorbed into the edits that your eyes forget what is within the range of ‘normal’ and what is not.

The more heavy your edits are, the more your sense of the norm tends to stray.

A practical way to tell if the colours in your photos are off is to pay attention to parts of the image that should be white or grey.

If the colour where it should have been neutral does not look neutral, you know that the colour adjustments need to be toned down and be more focused.

Creative effects

Photographers all have phases - one of those is the obsession with creative effects.

Trying out new things is great, and this is perhaps even a perk of being a beginner. Everything feels new and there is always this sense of accomplishment that comes with every attempt you make.

There will come a time though, when you look back and realise how thin a line it is between being creative and cliche.

There was a phase in my photography journey, where I really enjoyed the desaturated look, if not completely turning the photo black and white.

These shots are cool to see once in a while because it is an easy way to give photos a ‘wow’ factor; they are ‘moody’.

For quite an extended period of time I got carried away by gimmicky things like these without knowing that I was overdoing it and that I was not attracting viewers based on the merit of the photo itself, but merely the editing.

This is something to bear in mind though I’d have to say it does take some time for young photographers to grow out of it.

So have fun and enjoy what you are creating. If one day you wake up and see cliches in your photos, that is when you know you have developed a better eye as a photographer.

Do you really have to edit all your photos?

Whether to edit or not is largely a personal choice. While few in numbers, some photographers have developed a personal style based on no-edit images. The overall rule with photo editing is to keep it minimal and only make changes where actually necessary. So if based on the photographer’s professional judgment no editing is necessary, the image does not have to be edited.

Whether or not to edit an image also largely depends on your intended usage of it. Whether or not a photo is edited will probably not be much of an issue if the photo is made for an Instagram post.

In other situations, you might want to be more principled in your decision on whether or not to edit. For instance, if you are trying to convince a gallery to accept your work and distribute them on your behalf, you will need to defend every single thing you decide to do or not to do.

Another area in which photos are seldom left unedited is in book-publishing. Although photo are obviously the protagonist in photobooks, the process of making a coherent book inevitably involves a series of editorial decisions.

As a result, the photographer will most likely have to make some compromises so that the photos fit together as a collective to tell a narrative. They may need to be cropped, adjusted to be of a certain contrast level, have their colours fine-tuned etc.

The point is that it doesn’t matter whether or not you edit the photos; it is more about having a rationale to what you do and not do.

Basic photo editing tips for beginners

Use the histogram

The histogram is often overlooked by beginners, thinking that it must be useless because it is not an edit module in itself.

You are most certainly forgiven for thinking so - I was at fault of ignoring this golden tool for years since I started editing in Adobe software.

The point of the histogram is not to modify it directly; it is meant to provide a real-time update on the state of your image that is objective, in case you got caught up in the details and forgot about the big picture, which does happen quite a bit.

For your information, this is what the histogram looks like. Refer to the bit on the top right bracketed in orange.

A screen capture showing the histogram within Adobe Camera Raw photo editing software.

Whatever change you make in the sliders below, you have effected a change in the distribution of the pixels. The histogram will reflect these effects.

I might probably be quite old-fashioned in this regard, but I tend to agree with Ansel Adams that generally, pixels on a photo should span across Zones I to X.

If you know about the Zone system Ansel introduced to the analogue photography world, here I am applying it to the digital world.

In simple words, your photos should consist of a wide, balanced range of brightness values, from absolute blacks to absolute whites.

As I mentioned above, contrast is a defining feature of your editing style as a photographer.

And the histogram is the perfect tool to monitor the contrast level in your photos.

When I was just beginning in this, I thought that I could just trust my eye with brightness adjustments because they seemed straightforward. Plus, the histogram looked rather daunting.

Overtime, as I have learnt through producing some awfully ‘off’ photos, I always refer to the histogram as the ultimate quality control mechanism.

The human eye is way more deceitful than we’d imagine. The histogram is always honest.

Here are some examples of the type of mistakes I had made because of mishandling brightness in photos.

In this image above, the issue is that there are no whites, which should have been in the sky. There is also no real blacks, despite the edge areas looking quite dark.

This demonstrates how on the surface, an image might look alright to the human eye, but in reality is still slightly ‘off’.

With the histogram, I would be quickly able to tell that the pixels on this image isn’t quite meeting the two extremes on the brightness scale, and therefore go back in to fix things.

Of course, there is no need to be overly adamant about this, but it is a helpful general rule of thumb.

Pulled out another photo from my archives, edited when I was still too confident in my eyes to be bothered about the histogram.

Do try to figure out what is wrong with the photo before reading on!

3

2

1

This photo has no real blacks, and I had tried too hard to lift up the shadows.

Look at all the noise that is painfully visible, on the bricks and walls - had I paid attention to the histogram, I would have known that what the image lacked was more punchy blacks, not brighter shadows and mid-tones.

Without blacks, images tend to look muddy in the mid-tones. Unless you are deliberately going for the faded look, the blacks are a great way to give some body or substance, if you will, to an image.

Avoid dependency on filters and LUTs

Personally, presets have never worked for me. But they seem to work fine for everyone - I wonder if it is just me.

Which in retrospect could have been a blessing, because then I started developing my philosophy to photo editing without the reliance on presets, filters and the like.

Truthfully, unless the type of photography you do involves a highly repetitive workflow, and your work revolves around the same type of subjects, presets is a rather arbitrary way of starting your editing process.

There are professional photographers who utilise presets extensively, but that is because they are specialised in a certain area of photography and they do it in huge quantities over and over, every single day.

For instance, I know photographers who mainly shoot newborn photography in his studio, whose photo editing is done in a snap because they have presets tailor made for their photos.

But this works because 1) they shoot the same subjects, aka newborns in this case, and 2) they light their subjects in the same way every time and 3) their camera settings, exposure values are the same.

So presets would be useful if your workflow sounds like this.

But for the vast majority of us, this is far from what we do on a daily basis. The reality is, most photographers shoot a bit of everything, and we love trying out new styles and ways of doing things.

I myself, for example, work as a newspaper photographer. There is just no other day that looks the same as today. One day I would be shooting indoors in the government, another I would be shooting on streets under the scorching sun, the day after in the park under the snow.

My work as a photojournalist could perhaps put me on the extreme end in terms of the variety in the type of imagery I will have to process.

But my point is that ultimately, you will have to develop a compass that guides your photo editing inside of you, not outside.

Your photo editing style needs to come from within; do not attempt to have presets do it for you.

Finding your editing style is a difficult process, sometimes heartbreaking, if I am being honest.

You produce so much work that you absolutely hate and it takes so much patience to finally achieve the tiniest of breakthroughs.

But once you have developed your eye, it stays with you for the rest of your career.

It is not an easy path but one worthy of taking; it is worthy of you suppressing the temptation to just put on a filter.

Be principled in every edit

Photo editing can be a surprisingly logical process. It should, despite the fact that beauty often defies logic.

If I had to summarise amateurish-looking editing in one phrase, it would be ‘trying too hard’.

Perhaps it has to do with the excitement of discovering the array of things you can do with your photos in post-processing, as well as the desire to prove oneself; beginners tend to edit for the sake of editing.

When done well, photo editing indeed has the power to change how a photo looks drastically. But still, the first thing you see in a photo should be the substance of the photo itself, not the editing.

The best way to avoid going overboard with your edits is to come up with a justification to every step you take when editing a photo.

Where necessary, note down the changes you have made to a photo and what you intended to achieve by so doing.

You would be surprised by how often you contradict an earlier move by creating a new move that sort of undoes what you just did.

Or how often you make changes on autopilot, thinking that they are necessary, only to find that they are not actually serving your photo well.

The more logical and methodical your approach, the sooner you will find your groove in photo editing.

Should you edit film photos?

Yes, as long as you think your film photos need editing; this is the only rule in relation to editing film scans. Photographers should be free to apply any techniques that enable them to produce the results they envisioned, including editing. It is said that editing film scans destroys the authenticity of film photos, but in reality authenticity matters on the level of a photographer’s style, not the look of a certain film.

There has been a long-standing debate surrounding the issue of digitally editing film scans. Imho, whether or not you edit your film scans is entirely a personal preference, photographers should edit their film photos whenever they see fit.

The main argument against editing film photos is the fact that it defeats the purpose of shooting the film, because it changes the look of the film.

In response to this line of reasoning, here are some of my thoughts.

#1 Films are just the means to achieve a photographic goal; they are not an end themselves.

Honestly, in the professional photography world, no one cares about the materials and gear used to produce a certain body of work; it is the final presentation of the work that people are interested in, not what is used to create that work.

If a set of photos turns out to carry a great message or tell a great story, the last thing that matters is the film stock they were shot on.

As mentioned above, the job of a photographer is to take a creative vision and realise it in form of photos. This has not changed, across the analogue and digital eras.

Whether the film has been edited in the process is, frankly, irrelevant.

#2 The same negative can produce different versions of scans/ prints.

If you have done it yourself you would know - there is no one fixed version of what a given negative is capable of producing.

The act of scanning a negative inherently involves editing. To begin with, the brightness of the scanner already has an effect on the graininess and colours of the photo.

It is just a matter of who is doing the editing; it is yourself if you are processing your own film, and the lab technician if you are outsourcing the process to a lab.

The same negative will return different results depending on who is handling it. It is foolish to think that by editing your film photos they become less ‘original’ - there is no ‘original’ to begin with.

The darkroom printing process should also lend some insight into the role of the negative.

To make a darkroom print, seldom would you obtain a satisfactory print at the first go. Photographers typically go through the process of making a few test prints to figure out where the sweet spot lies in terms of contrast and exposure, before they go ahead with the actual print.

Apart from global tests, photographers also apply tests locally with techniques known as dodging and burning.

All of the test prints are then varying versions resulting from the same negative.

The very act of making a scan or a print is a form of editing.

#3 Editing is a technically necessary part of the analogue process.

I will just provide some examples that I can think of from the top of my head but this is by no means an exhaustive list.

Negatives tend to curve after drying; they all do, it is just a matter of extent. So when you scan a negative, it might not be perfectly straight and so cropping and perspective adjustments are required.

When shooting under highly contrasty lighting, you decide to expose for the shadows to secure a good density overall at the expense of the highlights being denser than you’d prefer. So you edit down the highlights to achieve the desired balance.

Films have a fixed form factor. 35mm is 3:2; medium format is commonly 1:1 square, 6x7, 4x5. Certain scenes work better with certain ratios so you might end up with unwanted space for a particular shot.

The quality of light changes throughout the day, say from neutral daylight to warm afternoon light to golden hour to blue hour. You only have one camera with you and have to shoot through all four scenes on the same roll. Some photos turned out too cool, some too warm. You therefore had to adjust the colours to match the photos with what you saw.

There are many more situations in which the need to edit very legitimately arises; these are just some scenarios that commonly happen to me.

How do I edit 35mm film photos?

Straighten and crop

Brightness adjustments

Colour adjustments

Here is a video in which I run you through my film photo editing process.

Summary

In this article, we talked about:

Whether professional photographers edit photos;

How heavily do professional photographers edit their photos;

What programs to use to edit your photos;

How to edit photos like a professional;

Whether you really need to edit all your photos;

Basic photo editing tips for beginners;

Whether you should edit film photos; and

How to edit 35mm film photos.

SUBSCRIBE via the box on the left for more PRO tips, and follow me on Instagram (@_bjiao__) and let me know what you think in the comments!

Share this article on Pinterest too!

Keep shooting, keep creating!

The mission of this blog is to provide the best insider information in the photography industry, as openly as possible. You have direct access to my

first-person experience as an aspiring photographer who talks, but also works.

Honest opinion are rarely available as public resources because this is a competitive industry. Huge sums are made when such information is delivered in the form of mentorship and workshops.

This blog is a great way in which I cover my daily expenses, but also provide real value.

If you have learnt something that would be worth at least $10, please consider donating to the page. This enables me to keep creating content and helping more people sustainably.

Your continued support for the blog is appreciated!